The

Life and Times of Shaykh Murtada Ansari

By Br. Abbas Jaffer

Introduction

and Biographical Information

Shaykh

Murtada bin Muhammad Amin Ansari was a

descendent of the Holy Prophet's

(S) noble companion, Jabir bin `Abdullah

Ansari. He was born on 18th

Dhul Hajj (the day of `Id ul-Ghadir)

1214/1799 in Dizful, Iran. For

20 years, he studied in Iran before leaving

for Iraq. After a briefstay there, he

returned to Iran. In 1249/1833 he decided to

visit the holy shrines

of Iraq, but this journey was destined to be

final, for here he started

his own classes in Najaf which made him

world famous.

He

studied under Sharif al-`Ulama' Mazandarani

in Karbala, Mulla Ahmad Naraqi

in Kashan and Shaykh Musa and Shaykh `Ali

Kashif al-Ghita in Najaf.[1]

After

the death of Shaykh Muhammad Hasan Najafi

(author, Jawahir al-Kalam) in

1266/1849, Shaykh Ansari emerged as the

undisputed marja` of theShi'is. He was to

become the most distinguished jurisprudent

of the Shi`ite world in the nineteenth

century.

He

died in Najaf in 1281/1864 at the age of 65

years.

Shaykh

Ansari's Personal Qualities

Shaykh

Ansari was famous for his retentive memory,

speedy resolution of intellectual

problems and his innovative teaching

methods.

Amongst

these novel teaching methods was the style

known as mas'ala sazi, which

involved constructing hypothetical legal

problems and then discussing all

the possible ramifications and resolutions

of the problem.[2]

His

personal character was beyond reproach and

he has been described as extremely

pious, leading a simple lifestyle. He

possessed a fair and just character.

His aversion to the accumulation of wealth

is demonstrated byhis practice of

immediately distributing bequests to the

needy and the students of religion.[3] At

his death he is reported to have left only

70 qaran(GBP £ 3.00 approx) [4]

The

Appointment of Shaykh Ansari

At

his deathbed, the sole Marja` of the time,

Shaykh Muhammad HasanNajafi, introduced

Shaykh Ansari as his successor. The

appointment of the 52 year old

Shaykh Ansari indicated the absence of any

scholar in the holy cities (`Atabat)

who could match his competence, knowledge,

reputation and influence.

Initially,

Shaykh Ansari invited his former classmate

from Karbala, Mulla Sa`id

Barfurushi Sa`id ul-`Ulama' (d. 1270/1854)

to assume the leadershipin

Najaf on the grounds that he was more

knowledgeable in the law. However,the latter

declined, arguing that although he had

indeed been moreknowledgeable during their

studies, he had subsequently been mostly

engaged in public affairs,

while Shaykh Ansari had been teaching and

writing, and was therefore,

more qualified for the role.[5]

Shaykh

Ansari's success in establishing his

pre-eminence was due to his personal

qualities as well as his background. Coming

from Dizful, a region with

a mixed Persian-Arabic culture, he could

teach in both languages and bridge

the ethnic divide between the Arab and

Iranian `Ulama'.[6]

His

Developments in Usul-al fiqh [7]

While

most Mujtahidin mastered one scholarly

field, Shaykh Ansari excelled in

both usul and fiqh. He introduced major

developments in the principlesof

jurisprudence that remain current to the

present day. His most important contribution

was in deriving a set of principles to be

used in formulating decisions

in cases where there is doubt. In this

regard he provided a new scope

to the discourse on fiqh. He divided legal

decisions into four categories:

Certainty

(qat`). This represents cases where clear

decisions can be obtained

from the Qur'an or reliable Traditions (ahadith).

Valid

Conjecture (zann mu`tabar). This represents

cases where the probability

of correctness can be created by using

certain rational principles.

Doubt

(shakk). This refers to cases where there is

no guidance available from

the sources and nothing to indicate the

probability of what is the correct

answer. It is in relation to the cases that

Shaykh Ansari formulated four guiding

principles which he called Usul

al-`amaliyya[8] (practical principles).

His most important work, al-Rasa'il (Fara`id

al usul) is taken up explaining those.

Erroneous

Conjecture (wahm). This refers to cases

where there is a probability

of error; such decisions are of no legal

standing.

The

effect of the developments instituted by

Shaykh Ansari was far-reaching.

Previously

the Mujtahidin had confined themselves to

giving rulings where there

was the probability or certainty of being in

accordance with the guidance

of the Imams (A). However, the rules

developed by Shaykh Ansari allowed

them to extend their jurisdiction to any

matter where there waseven a possibility of

being in accordance with the guidance of the

Imams (A).

This

effectively meant that they could issue

edicts on virtually any subject. Shaykh

Ansari's own strict exercise of caution (ihtiyat)

severely

restricted this freedom, but some

other Mujtahidin allowed themselves a

freer hand.

Differing

Ideologies and the Political Backdrop to the

Period of Leadership of Shaykh Ansari

Towards

the end of the lifetime of Shaykh Muhammad

Hasan Najafi, the major concerns

of the `Ulama' were the conclusion of the

Usuli-Akhbari conflict, the

appearance of the Shaykhi and Babi movements

and contending with the Qajar

and British rule.[9]

The

Akhbari School. Although a part of the

mainstream Twelver Shi'ism from is

earliest days, this school crystallised into

a separate movement following

the writings of Mulla Muhammad Amin

Astaraabadi (d. 1033/1623).

It achieved its greatest influence during

the late and post-Safavid periodsbut was

crushed by the `Usuli Mujtahidin at the end

of the Qajar era. Essentially

the Akhbari school accepted Qur'an and Sunna

in matters of doctrine

and law, while rejecting consensus (ijma` )

and intellect (`aql).The

contribution of Shaykh Ansari in

strengthening the `Usuli position

is well recognised.

The

ShaykhiSchool. Whereas the Akhbari school

differed from the `Usulis principally

in matters of furu`, the Shaykhi School,

founded by ShaykhAhmad ibn

Zaynu'd-Din al-Ahsa'i (d. 1241/1826),

differed principally in usul.

There

is evidence that Shaykh Najafi made attempts

to marginalize their role,

but there is no information about Shaykh

Ansari's direct confrontation against them. The

Babi movement started when Sayyid `Ali

Muhammad Shirazi (d. 1263/1850)

took

the title Bab and in time declared that the

Shari`a was abrogated and brought

a new religious book. Shaykh Ansari reacted

by enhancing religious awareness

in the smaller towns by setting up religious

schools funded by Khums

revenue.

Shaykh

Ansari largely ignored both Qajar and

British influences, and appeared

apolitical. Although he reached an agreement

in 1852 with the British

consul Rawlinson on the distribution of

bequest funds in Najaf, he subsequently

withdrew from the distribution in 1860, when

he suspectedthat the bequest was a British

ploy to buy influence amongst the `Ulama'.[10]

After

the Death of Shaykh Ansari

Shaykh

Ansari did not introduce a successor to his

position although he was

well aware of the capability of his

students. He may have preferred the practice

of choice (tarkhis) in selecting the marja`

[11]. After his death no

single figure immediately assumed his

position. For a period of atleast ten years,

the Shi'ite leadership was divided between

the more capableMirza Hasan Shirazi (d.

1313/1895) and his seniors Mirza Habibullah

Rasti (d. 1312/1894)

and Sayyid Husayn Kuhkamara'i (d.

1299/1882), who was popular among

the Turkish speaking Shi'is. Only after the

death of Sayyid Kuhkamara'i

and the withdrawal of Mirza Rashti did Mirza

Hasan Shirazi

emerge

as the sole supreme source of emulation for

a period of twenty-one years.

The

Lasting Impact of the Work of Shaykh Ansari

Shaykh

Ansari provided the groundwork for the `Ulama'

to issue fatawa (edicts)

on virtually any legal problem by giving a

new scope to the application

of legal theory, especially that of al-`usul

al-`amaliyya - discussed

earlier. He also introduced the notion that

it was necessary for the

community to follow the opinion of a

Mujtahid.[12]

This

idea was transformed subsequently by

Tabataba-i Yazdi (d. 1337/1919) into

an initial prerequisite for every Shi'i

reaching the age of

responsibility

(taklif). Eventually, it became a commonly

held view that the performance of Islamic

duties (such as prayer and fasting) are void

without doing the taqlid (emulation) of a

marja`.[13]

This

has indeed contributed to the authority of

the `Ulama' not only in the juridical but

also in the political sense.

Conclusion

Shaykh

Ansari was a genius of extra ordinary

calibre. In Usul and Fiqh,his originality

and analytic mind enabled him to blaze a new

path, a pathwhich has been adopted and

followed by all the subsequent Fuqaha. His

two great works,

al-Rasa'il in Usul and al-Makasib in Fiqh

are an inalienable partof the curriculum in

modern Hawzas.

He

established conclusively the dominance of

the Usuli position againstthe neo-Akhbari

Traditionism and completed the work started

by Muhammad Baqir Vahid

al Bihbihani (d. 1205/1791) in this regard.

Amongst

the Shi'i Fuqaha, the figure of Shaykh

Murtada Ansari towers high. He

certainly is the most famous marja` of the

pre-Modern Age, and isrightly known as

"Khatimul Fuqaha wal Mujtahidin" -

the Seal of theMujtahidin.[14]

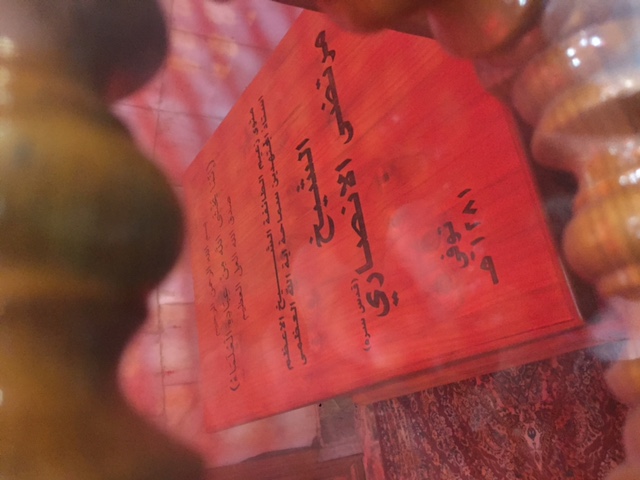

HisGrave at the entrance to Imam Ali shrine

on left side when entering from Bab Qibla

Further

Reading

Jaffer,

Asgharali M.M., Fiqh and Fuqaha, World

Federation of K.S.I.M.C., London,

1990.

Litval,

Meir, Shi`i scholars of nineteenth-century

Iraq, CmbridgeUniversity Press,

1998.

Momen,

Moojan., An Introduction to Shi'i Islam,

Yale University

Press,London, 1985.

Moussavi,

Ahmad Kazemi. Religious Authority in Shi'ite

Islam,

International

Institute

of Islamic Thought, Kuala Lumpur, 1996.

References

[1]

Asgharali M.M. Jaffer, Fiqh and Fuqaha, p.

38

[2]

Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i

Islam, p. 202

[3]

Sayyid Muhammad Kazim Yazdi, al `Urwatu'l

Wuthqa, p.4

[4]

Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i

Islam, p. 311

[5]

Meir Litval, Shi`i scholars of

nineteenth-century Iraq, p. 71

[6]

Meir Litval, Shi`i scholars of

nineteenth-century Iraq, p. 71

[7]

Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i

Islam, p. 186,187

[8]

Briefly, the Usul al-`amaliyya consist of

al-bara'a:

Allowing the maximum possible freedom of

action.

al-takhyir:

freedom of selecting the opinions of other

jurists or evenother schools of law.

al-istishab:

the continuation of any state of affairs in

existence, or

legal decisions already accepted unless the

contrary can be proved.

al-ihtiyat:

prudent caution whenever in doubt.

[9]

Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i

Islam, p. 135

[10]

Meir Litval, Shi`i scholars of

nineteenth-century Iraq, p. 71

[11]

Ahmad Kazemi Moussavi, Religious Authority

in Shi'ite Islam, p. 204

[12]

Murtada Ansari, Sirat al-Najat, p. 1

[13]

Commentaries by a number of contemporary `ulama'

on Yazdi's al-`Urwa,

pp

3-4

[14]

Asgharali M.M. Jaffer, Fiqh and Fuqaha, p.

39